-

Road safety and elderly drivers.

September 03, 2019

Road safety and elderly drivers.

Earlier in the year Prince Philip, the 97 year-old husband of Queen Elizabeth the II of Britain was involved in a car accident, in which the vehicle he was driving collided after he failed to see the oncoming vehicle which had the right of way. This incident re-opened the age-old discussion on how old is too old to drive. Upon reaching a certain age threshold should elderly drivers be stripped of their car keys and taken off our roads? Or as a society should we be looking at alternatives and how we can assist the elderly extend their driving for as long as it is practical and safe for them to do so?

“Driving is all about independence and one of the most

emotional things for anyone to give up..”

- - Andy Cohen, CEO/Co-Founder, Caring.Com -Does the ageing process affect driving ability?

After years of experience behind the wheel the art of driving appears to come naturally, a skill we never forget, just like riding a bike. However, in reality, although we may not give it much thought, it is an intricate function that requires a mix of visual, cognitive and physical skills. Unfortunately, as people age, although they are mostly safe and cautious on our roadways there is a deterioration in many of these abilities considered as necessary to safely operate a motor vehicle.

The aging population in Australia and New Zealand, as well as many other countries around the world, is growing at an exponential rate. With the technological and medical improvements in society, people are living longer and driving longer, along with the baby boomers ‘coming of age’ the age distribution of our population is changing. People over the age of 65 are making up a larger proportion of the population, as a result, there are more elderly drivers on our roadways than in previous generations, a trend that is expected to continue well into the future. This reality indicates that elderly drivers will continue to have an impact on road safety and needs to be considered as part of any traffic safety strategy.

As we age our ability to process information and our reaction times are generally slower than they were in the heyday of our youth, making driving more complicated. With our elderly population better able to maintain their independence, they are also holding on to their drivers’ licenses for longer. However, this independence comes with an increased public concern in relation to sharing the road with them. There are many factors that impair our driving skills as we enter our golden years, namely:

- Decreased vision

- Impaired hearing

- Slowed motor reflexes

- Medications

- Reduction in strength, coordination, and flexibility

- Judgement and decision-making skills

- Worsening medical conditions

These factors, or a combination of these factors, can make it difficult for elderly drivers to see road and traffic signs effectively at night, hear critical warning or surrounding sounds, hard to grip and or maintain a firm hold on the steering wheel or difficult to step on the brake pedal at the drop of a hat. Some of these difficulties can be overcome to assist the elderly on our roads, for example, most modern vehicles are equipped with automatic transmission, power steering and power brakes to compensate, when safe to do so. Those who suffer from hearing loss can utilise hearing aids when driving to ensure they can effectively hear their surroundings. In some circumstances, the use of a driver rehabilitation specialist and appropriate individualised adaptive devices can also help elderly drivers to stay on the road safely, for longer. However, when it comes to vision, there is only so much that a pair of glasses can do to help, and thus eye conditions, diseases, and vision impairments associated with aging represent a larger segment of our societal health challenge on a population basis than in previous decades. Older drivers need more visible road signs and pavement markings to help counter the eyesight degeneration and diseases that come with getting older.

It is interesting to note that studies suggest there is universal agreement that ageing amongst the elderly, even the normal ageing process, correlates with the increased susceptibility to a variety of medical conditions, of which many carry significant safety implications to driving safely on our roads. Stutts and Wilkins1 summarised much of the research as follows: As a group, older drivers have poorer visual acuity, reduced night time vision, poorer depth perception, and greater sensitivity to glare; they have reduced muscle strength, decreased flexibility of the neck and trunk, and slower reaction times; they are also less able to divide their attention among tasks, filter out unimportant stimuli, and make quick judgements.

Ageing and your eyes.

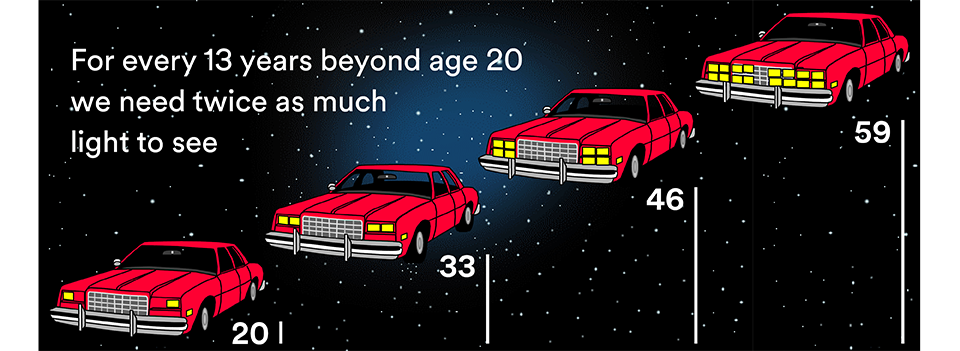

What we see during the day is not always what we see at night, just 5% of the information we see in daylight are caught by the eye at night. As we age, for every 13 years beyond age 20, we need twice as much light to see. Older drivers require approximately 40% more time and 8 times more light to respond to a sign or an object than younger drivers do.

So what happens to our eyes when we age? First, to understand how our eyes change when we age, it helps to grasp the basic workings of an eye functioning at its full capacity. In a typical healthy eye, like miniature cameras, they process the light that travels through the front of the eye (the cornea), through the pupil and then the lens, which focuses it and directs it to the retina at the back of the eye where it forms an image. This image is then converted into electrical impulses that are sent via the optic nerve to the brain and interpreted as the sight and vision that allows us to see.

The retina contains specialised cells that respond to light called photoreceptors, there are two types; cones and rods. Cones are sensitive to colour and work only in bright light, thereby enabling us to see when it is light. They are abundant in the macular area of the retina and provide us with colour vision and the ability to detect fine details like the words on this page. Rods are light-sensitive and respond best in darkness and dim light, they are very receptive, especially to motion. They provide only black-and-white images and thus are critically important for night vision.

As you get older, the muscles in your iris that control the size of your pupil weaken and have trouble understanding how much light to let in. Aging eyes also begin to lose the rods that help them detect motion. In her New York Times article ‘Growing Older, and adjusting to the dark’ Jane E. Brody2 states that: “In the young eye, rods outnumber cones by nine to one in the part of the retina called the macula. But an autopsy study of older adults found that while the cones remained intact, almost a third of the rods in the macula had been lost.” The result of these less receptive iris muscles is a slower adaptation to the intensity of light. This directly impacts a person’s ability to drive safely, as the eye is constantly working to adjust to changes of brightness on the road. “In older eyes, this phenomenon, called dark adaptation, takes longer, which means you see less well in the dark after being in the light, and vice versa. The diminished number of rods may be a factor, but in addition, the light-sensitive pigment in the rods regenerates more slowly in older eyes.” according to Brody.

Seeing is believing.

Globally, the population aged 65 and over is growing faster than all other age groups. According to data from World Population Prospects, the 2019 Revision, by 2050, one in six people in the world will be over age 65, up from the current figure of one in 11. This segment faces the natural decline in sensory, cognitive and physical function that can adversely affect driving making it more of a challenge. Prolonging the mobility and independence of older adults, when safe to do so, is an important social goal. These drivers need more visible signs made with high-performance reflective sign sheeting, higher sign luminance provides enough returned light to the driver so they can read and comprehend signs before they move out of view. More accurate sign reading and less eyes off the road provides more reaction time and helps reduce traffic accidents.

Driver safety is our top priority, with the highest luminance values at the distance that matters most, 3M™ Diamond Grade™ DG3 Sheeting helps to reduce crashes and fatalities. To see first hand the power of how better visibility signage can increase safety, register for an in-office demonstration. We would love to come and see you and your colleagues and run a workshop around the Science of Advanced Signage. We can tailor the workshop around any or all of the topics listed below:

- Critical roles of traffic signage

- Science of retro reflectivity

- Science of fluorescence

- Human factors affecting sign visibility

- Environmental factors affecting sign performance

- Do sign upgrades improve safety?

- How to apply best practice in traffic signs

Register for the

workshop today!For more information about reflective sign sheeting and performance levels to meet the needs of your specific application view our Traffic Signage brochure, explore our website, or contact your 3M Transportation Safety Expert.

References:

1. Stutts, J. and Wilkins, JW. (2003) ‘On-road driving evaluations: A potential tool for helping older adults drive safely longer’, Journal of Safety Research, 34, pp. 431-439.

2. Jane E. Brody. (2007) ‘Growing older, and Adjusting to the Dark’, The New York Times, 13 March, p. F7.